[The] pursuit of freedom within the photographic frame, of subject matter and aesthetics remains Stieglitz’s hallmark and legacy to American art. It always took him beyond whatever anyone else had achieved. In order to do that it was, as artist Georgia O’Keeffe noted about Stieglitz in 1978, ‘…as if something hot, dark and destructive was hitched to the highest brightest star.’1 The loftiness which Stieglitz seemed to cultivate, his acolytes in the 1930s and 40s were only to keen to affirm. However, although Stieglitz’s signature photographic view of the world was generally straight across, he looked up to photograph clouds and people or trees framed by the skies in a dynamic relationship, but he did not look toward the ground. In 1927, for the first time in that a print is extant, he photographed the rain on the grasses at Lake George.

This sublime little picture, with its curving long grass stalks gracefully bending under the weight of the raindrops, takes the delicate balancing act apparent in the more known Gable and apples 1922 – where raindrops, apples, bough of the tree, house and sky are composed into a visual haiku – and pushes toward total abstraction. This is an abstraction anchored in the earthly and organic as the dynamic of light, water and curves makes clear. There are very few other existing photographs by Stieglitz in this vein and they only reappear in 1933/34. The glinting of light on water, however, was not rare in Stieglitz’s work and clearly it was a preoccupation from the 1910s onward, first appearing in the photogravure The City of Ambition 1910 with the sun bouncing off the Hudson. The glint becomes more pronounced in 1916 when he photographed Ellen Koeniger at Lake George and printed in gelatin silver so that the twinkling of light on water is sharper. The symbolism associated with this sparkle of generative forces meeting is also apparent in the way in which Stieglitz would print portrait heads of say, O’Keeffe or Margaret Treadwell, among others, in the early 1920s, highlighting the glistening of their eyes.

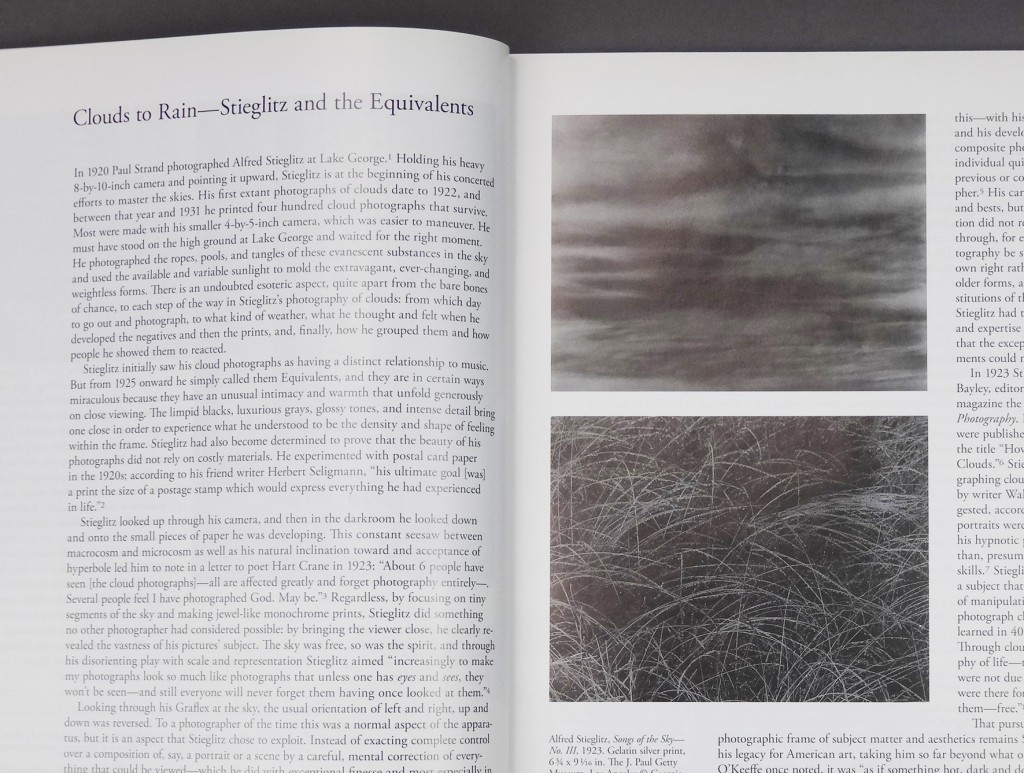

Nature at Lake George came to be the touchstone for Stieglitz – in viewing the landscape and the skies he could check his own being: ‘Lake George is in my blood, the trees and lake and hills and sky’, he wrote in 1914.2 Though he never seems to have photographed the Lake excised from its surrounds or for its own sake, its place between the hills and under the sky is omnipresent. Like Henry Thoreau’s remark about the qualities of such a body of water: ‘It is Earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature,’ that eye is reflected in the sky in many of Stieglitz’s cloud photographs.3 This is most especially true in the darkest and moodiest of the Equivalents – amongst those photographs that he came to view as the equal to life’s experience.