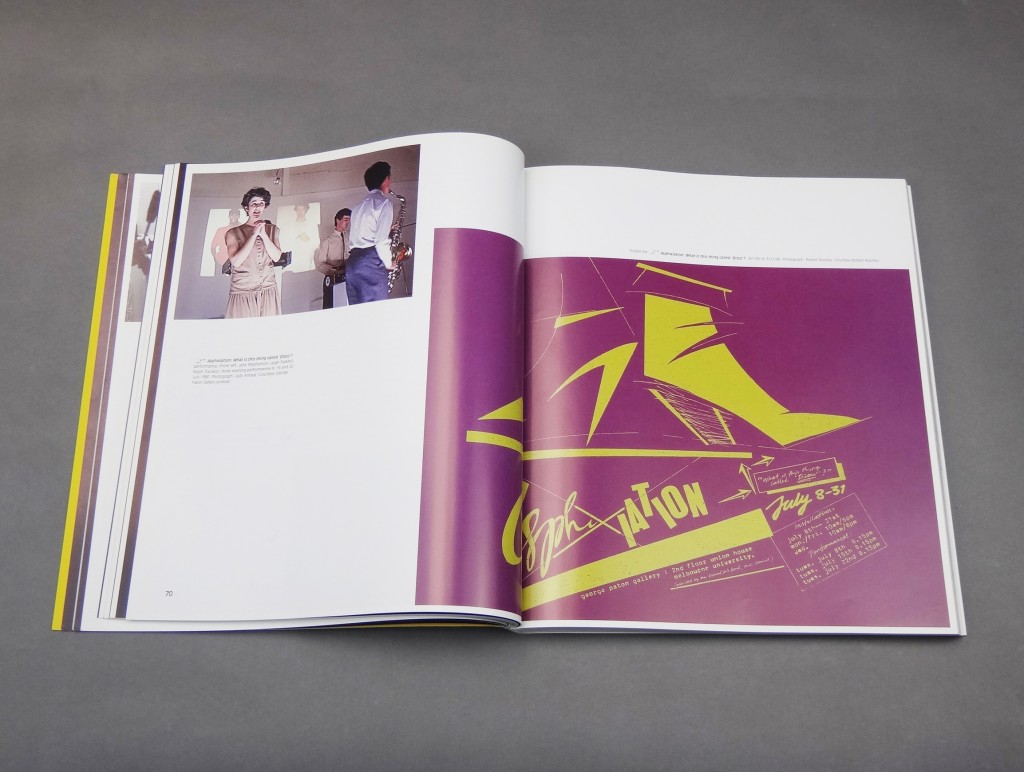

The George Paton Gallery was the central point for alternative art practice in Melbourne through the 1970s and early 1980s, until the opening of Gertrude St Studios in 1985; it operated as an exhibition space, an archive, an information space, a generator and supporter of publications (Art Almanac, Arts Melbourne, LIP and Art & Text), and a venue for poetry readings, performances of various kinds, film screenings and lectures. It was the one place interstate and international visitors could confidently approach for information about the contemporary and experimental Melbourne scene. A conduit, generator and incubator, the George Paton Gallery saw itself as alternative to the mainstream politically, aesthetically and conceptually.

In the late 1970s, ‘alternative’ meant anything not embraced by the art museum or most dealers1 and in Melbourne this encompassed performance, interdisciplinary work, various forms of installation, and new media such as experimental video, film and sound. Providing a voice and a location to artists ignored by the majority of institutions (including those artists who worked with forms of painting, photography and sculpture which such institutions deemed inappropriate), was considered by the George Paton Gallery staff and contemporary artists to be of great importance. Within each discipline or marginalised group there tended to be hierarchies, stratifications and specificities which defied the constant attempts by the mainstream to categorise and flew in the face of the prevailing notion of ‘key works by key artists’. An expanding field of practices and positions remains vital, now as then, to the health of contemporary art. This was not necessarily seen to be so at this time. The perspective, that without artists making art there could be no institutional structures, that is, all other aspects of the art world could not exist was not a popular one: the rights of the artist and their work should be paramount whenever possible with the curator working in parallel as a facilitator not as the dominant force.

Interestingly the George Paton was never run by artists despite the emphasis on the Gallery being a platform for artists rather than curators or administrators (though Aleks Danko and Vivienne Shark LeWitt did work there at various times). It took the intervention of English artist Mary Kelly rather than the Australian Artworkers Union before artist fees were formalised as an essential payment for work done.

By 1982, ‘alternative’ spaces such as the George Paton Gallery, Adelaide’s Experimental Art Foundation and the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art had agreed they were henceforth to be known as ‘contemporary art spaces’ and all were encouraged by the Australia Council to embrace the bureaucratic procedures required for firmer funding. At the time this was seen as useful protection, especially for the George Paton Gallery, which tended to be viewed as an anomaly by the institution that housed and funded it, the Melbourne University Student Union.

The change in description from an ‘alternative art space’ marked the beginning of the transition in Australia away from the idea of the outsider or the marginal as a viable anti-institutional stance. The transition would reach a form of completion in the mid 1990s with the advent of less oppositional notions of hybridity and the post-colonial.

The period 1979–1982 , during which the George Paton’s designation moved to a ‘contemporary art’ space, represented a generational and conceptual shift in policy at the gallery: toward the research and care of the Ewing Collection of early 20th century painting which had languished under the rush of experimental activity through the 1970s; away from the gallery being seen by some emerging artists as a stepping stone to a dealer’s stable; and toward finessing the program of contemporary activities.