The Los Angeles-based artist Shannon Ebner uses photography specifically as a linguistic tool. Her practice is steeped in photographic knowledge, as she has previously acknowledged: ‘From Atget to Ruscha…with Evans, Kruger and Holzer hanging out in the same crowd as Shore, Friedlander and even Man Ray.’1 Ebner’s understanding of the power of the word comes in part from her work in New York City in the 1990s with the American poet Eileen Myles and her interest in writers such as Francis Ponge. It also comes from the ‘atmosphere’ of the dynamic spoken word traditions of the US, where the ability to declaim is prized and, in its most refined forms in which an elegantly deceptive simplicity is key, unrivalled.

The mélange of image and word in Ebner’s photography began in the 2000s when she moved to Los Angeles after completing postgraduate studies at Yale University. Her first major body of work, Dead Democracy Letters, seemed to spring up fully formed when she showed it at the New York gallery Wallspace in 2005, yet it was the fruit of more than a decade of thinking. Dead Democracy Letters 2002–06 put a finger on the times in the US, turning back on the viewer the desiccated and paranoid political landscape that had overtaken the country since September 11, 2001. More than polemic however, this body of work drew broadly on visual histories. Ebner planted cardboard letters in the southern Californian landscape, evoking miscued versions of the Hollywood sign. Moving between urban environs such as the La Brea tar pits, the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean and desert areas like Joshua Tree, she created words within images that belied the inevitable frozen nature of the photograph. The mobility of her thinking and picture making also reflected a collision between the gritty black-and-white realism of Robert Frank’s The Americans 1958 and the deadpan wordplay of Ed Ruscha. Ebner eventually folded up her cardboard letters, filed them in a coffin-shaped box on legs and photographed the dismal object on an empty road, making the work Sculptures involuntaires 2006 – in homage to Brassaï’s practice as much as in reference to any other consideration.

Ebner extended the idea of the found object in 2008 when she began using cinder blocks to make words, then photographing the blocks – which are usually installed on large pegboards – to make concrete poetry literal. These blocks are commonly used to build walls and cheap housing; Ebner thereby extended the metaphor in her ongoing meditation on the recent wars the US had entered and the walls that were being built in the Middle East. From a distance, the cinder-block works look like giant ruled pages from an exercise book, the words printed in what could be an early computer font. The letters spell out an uneasy stream of consciousness commenting on contemporary life, as can be seen in Strike/ 2008, which is loaded with palindromes, and the book The Sun as Error 2009, published by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The pictogram of the golden-rayed sun that graces the cover of The Sun as Error is also an asterisk—the computer code for an error—and the book is full of collapsing signs made or found by Ebner, as well as unexpected views. There is a level of the whimsical as much as there is mordant wit in Ebner’s work, which elevates it from being merely didactic. The large format but slim book that she produced with the designers Dexter Sinister has a slightly retro feel with its tantalizing gray-scale images of words, places and people slipping in and out of signs. Ebner has noted, ‘I wanted the book to be more of an open-ended reading of the work.’2 And she acknowledges the debt to MIT Press’s visionary design director in the 1970s, Muriel Cooper, who produced the asterisk symbol that continually appears as a repositioning sign in The Sun as Error.

The asterisk reappeared in Ebner’s solo exhibition at Wallspace in 2009, where almost all the photographs bordered on the minimalism of Agnes Martin or the abstraction of Brice Marden. As is usual with her practice, the various works were a variety of different sizes, and there were sculptural elements as well, both found and made, all of which pointed toward things in the world. Ebner commented at the time, ‘I am looking for a way out of the problems of representation but I am not satisfied to leave the world of representation altogether. I am somehow looking to stay in the world of depictive images by simply asking for more from them through developing a different system, idea or model of how they might function.’3

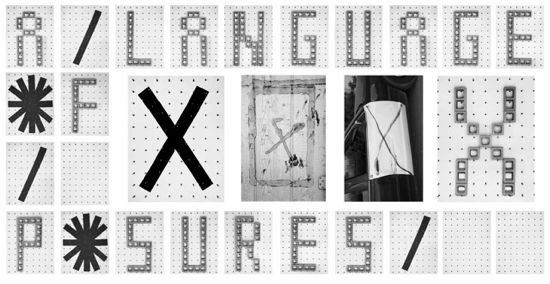

An inkblot might look like a menacing typhoon and clouds seen through a dirty window could still seem romantic; blank grids ask us to fill them with meaning. In her large scale work for the curated exhibition of this year’s Venice Biennale, The electric comma (A language of exposures) 2011, there is a further play on the shape and sound of letters, with four Xs appearing (two found and two made), plus two suns (or are they errors, or simply asterisks?), and three backslashes. This is what is magical about Ebner’s work: that there is always this hook by which she takes what we think we know and stretches it out into what we may not know at all. Whether she uses an image or a word or both together, she teases the imagination. Photography aids in this confusion with its strange ability to be both a flat surface and an imaginary world, imprint of the real and the barely tangentially related. What she wants to say is utterly serious in its playful collisions of word and image.