In the catalogue for the exhibition she organized in 2007 at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum, All About Laughter: Humor in Contemporary Art, curator Mami Kataoka wrote that one of the most important functions of art is to ‘toss a stone into the still waters of our customary patterns of thought and perception and make a splash.’

It’s that ‘splash’ that opens a space where dialogue between word and mind, mind and object and object and person can truly take place. On display in that same exhibition were the videos of Takayuki Yamamoto, chiefly those from the artist’s Teaching Spoon Bending series begun in 2001. For this project, Yamamoto works with children from different cultures, teaching them the Israeli-born celebrity paranormalist Uri Geller’s method of psychic spoon bending.

Also an elementary school teacher in addition to working as an artist, Yamamoto reveals through his video activities various preoccupations, most of which center around children. One such preoccupation is how to correctly wash a car, another is the idea of protection from calamities. Then there is the strange disconnect where children happily create imaginary environments to which they themselves may be sent for punishment.

Part of the appeal of much of Yamamoto’s work is in the directness with which the children communicate with the artist and camera and how he makes this apparent. One cannot say the communication is unmediated because the children are already at a school-going age and are aware of their surroundings. Further, Yamamoto constructs the environments and briefs the children so that even though what they say and do may appear immediate, it cannot be completely so. Nonetheless, the sheer charm of Teaching Spoon Bending is acknowledged in the title itself, which embodies a contradiction between the practical, ‘teaching,’ and the impractical, ‘spoon bending.’

Yamamoto creates a specific space for his camera and therefore for viewers as well: each student sits at a desk in the foreground, parallel to the picture frame. Viewers take the place of the teacher who is also in the position of the camera. Visible in the background are the rest of the class, watching and practicing their spoon bending. Each child then appears at the front of the class to demonstrate their abilities, much as they would do if they were reciting any other kind of lesson. The options for pass or fail, if considered seriously in this instance, are diabolical.

Generally speaking, only the most gullible person would believe that spoon bending by mental powers alone is possible, but on the other hand the suspension of disbelief and the illusory nature of things can provide respite from the mundane and lead us involuntarily to that artistic ‘splash.’ How can spoon bending happen? That the children willingly pursue the possibility is clear from Yamamoto’s videos, but when their spoons do bend their mixed expressions of astonishment and relief – and every shade in between – reflect anxieties adult viewers may have forgotten and can momentarily relive.

Yamamoto’s work is never blandly vicarious. In his 2010 video New Hell, he asks children to construct places that they regard as ‘hells’ to which they might be sent. The children are then recorded explaining how their painted cardboard structures function. These videos are shot in a shallow space with the children in the foreground indicating the salient points of the hells they have created, recalling a TV weatherperson advising viewers on whether or not to take their umbrellas when they leave for work. The combination of the children’s cuteness, their eagerness to please an authority figure and the fact that they are devising systems for inflicting pain upon themselves is bitter and sweet. And, perversely, viewers can admire the children’s inventive constructions and their corresponding imaginative descriptions.

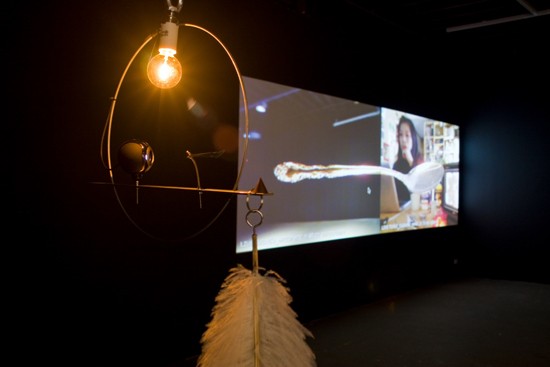

In Sydney in 2009, the Japanese collaborative duo exonemo exhibited a similarly resonant work, an online installation entitled Supernatural. Unable to take up a preparatory residency at the nonprofit Artspace, which hosted their exhibition, due to the impending birth of their daughter, the two artists devised a work that harmonized art and life, distance and proximity, grasping and giving, the physical and the incorporeal and the apparently natural and the possibly supernatural. This elegantly simple work featured the handle of a spoon hovering in the darkened gallery at Artspace, and its other ‘scooping’ half hanging in exonemo’s home and studio in Tokyo. On a long wall in Artspace, the two halves of the spoon were projected joined together, the Sydney half on the left and the Tokyo half on the right.

From the vantage point of Artspace, viewers could communicate in real time with exonemo in Tokyo and observe their daily routines, which they carried out in front of a webcam. The artists, correspondingly, could track visitors and their reactions by computer. Apart from the large projections seamlessly joining the spoon images, the only other thing on view in Sydney was, at the entrance to the gallery, the lit half of the spoon and another tiny webcam that operated like an extended eye, both balanced on a thin, mobile-like rod anchored by an ostrich feather.

In a sense the spoon was spooning itself, having been severed and then put back together again in cyberspace. Supernatural made the dual act of seeing and imagining in tandem a profoundly physical experience. This alone gave the work significance in spite of its apparently limited tangible properties. Indeed, some art works communicate precisely through their immaterialness. Because they maintain an exclusively screen-based existence, they can only and most potently leave a residue in the mind or imagination. Supernatural also had an element of dynamism thanks as much to its spatial composition as its ideas and visual manifestation. The eye of the webcam, the feather, the severed spoon handle and the split screen projections joined by the whole spoon image seemed like fanciful escapees from a 21st-century take on Alice in Wonderland, or writer William Gibson channeling surrealist artist Joseph Cornell in order to make the universe turn.

exonemo’s kind of cut-and-paste, which is both the literal process that they used to make the work and a constantly updated process occurring in real time and across cyberspace, advances the 20th- century collage traditions found in literature and art. It seems to be an intensely human drive to present through art the complex layerings of interactions that arise within the imagination or those that arise from a dialogue with others. The idea of creating interactions to see what might result is also relevant here. The corresponding drive to translate images and ideas from the imagination or from such dialogues can become, insidiously, a drive to homogeneity when the artist’s primary concern is anticipating the audience’s requirements. It is therefore useful to consider what critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote in 1923: ‘Just as a tangent touches a circle lightly and at but one point … a translation touches on the original lightly and only at the infinitely small point of the sense, thereupon pursuing its own course according to the laws of fidelity in the freedom of linguistic flux.’ That light touch is like the splash that can result in an eruption or generate ripples, and retain a truth as well as liberate a range of meanings.